If you would like to listen, there's a very fine recording by James Kibbie here. You can either download the tracks, or let them open in your computer's media player.

If you would like to refer to a score, you'll find it here.

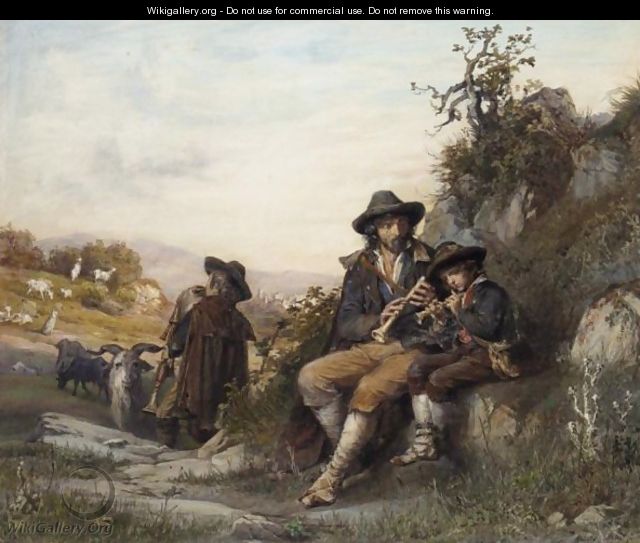

Many of us play pastoral-inspired pieces at different times of the year for a variety of reasons. The liturgically single-minded might schedule a pastoral piece for a Sunday where the readings dwell on the image of the Good Shepherd, or anything involving the newly-born, livestock or pets, such as Christmas Eve or St Francis’s day. I’m sure barely a Christmas goes by without someone playing the Pifa from Messiah for a crib service, or as a quiet interlude during a well-attended carols pageant.

The pieces which make up Bach’s Pastorella were probably not intended to be a unified set in the way we see it, mediated as our view is through a century-and-a-half of edition-making. Peter Williams highlights the difficulty of making too many sweeping claims about the aesthetic unity of this piece: ‘it is possible that the whole work was composed/compiled for some unknown occasion – but also that movements 2, 3, 4 have nothing to do with the first, to which alone the title “Pastorella” applies, whatever “ingenious synthesis” the whole work might be said to achieve...If it could ever be shown that in its present form BWV 590 is authentic, it would be a unique imitation, contrapuntally worked, of four Italian genres: pastorale, allemande, aria, giga.’ (Peter Williams, The Organ Music of J.S. Bach, 2nd ed., Cambridge: CUP, 2003, p 197.)

Each of the movements maintains a drone in some way, like a hurdy-gurdy or bagpipe played in the meadow. The first and second movements achieve this through pedal-points across several bars, the third by a very slow harmonic rhythm, and the fourth by constant return to a motivic centre on the accented beats.

The first movement should be played on one manual, and is the only one which uses the pedals. As ever, you would be well served to choose your registration carefully. The major point to bear in mind is that the stops you choose should speak well and have a good deal of colour to them. Although the edition linked here only gives a couple of ornaments, you should view this as a guide for further elaboration using similar figures in both hands. While this movement is nominally in F major, it ends rather surprisingly with a full close in A minor.

This trip into mediant harmony at the end of the first movement provides the springboard into the second movement, which is firmly in C major. This movement is clearly intended for performance on a single manual, but given that the two sections are repeated, there is scope to have contrasting registrations set up on different manuals. One needs to be careful of getting too sentimental about this movement: it is very sweet, but you should avoid getting too wet.

The third movement flips the mode, taking us into C minor. The pulsing chords in the accompanying line underpin the slow harmonic rhythm. This allows Bach to ‘walk around’ the key and explore its properties, which gives this movement a slightly improvisatory feeling. The melody is unmistakably Bachian. This movement could be played on a single manual, or with the top line as a solo. In this case, you might not want to follow the Novello edition’s rather passé suggestion of the Orchestral Oboe as the solo colour. Unless it’s particularly special, a reed really isn’t the right sound for this movement. You should explore to find the right solo colour on your instrument.

The final movement takes us back to the home key. This is a lively giga, although there is plenty of Bach’s fugal approach here. The piece is built around a semiquaver motif which circles around a tonal centre in each entry: C-G-C in the first section, C-F-C in the second. Use this concentration on tonal centres as part of your strategy for practising this piece: if you concentrate on anchoring your fingering pattern around the repeated notes, it should make preparing for performance a much more relaxed process. One of the compositional tricks I enjoy in this piece is that everything is turned upside-down in the second section: it feels a bit like crawling over the monkey bars. This movement calls for a bolder registration. You might consider some variation of 8, 4, 2, or a small principal chorus up to mixture. The main point is that this piece has to sparkle with charm, wit and humour.

Given the sunny mood of the Pastorella, it could serve well for a feast day, or during the long stretch of green Sundays after Pentecost. It is a firm feature of my wedding and funeral repertoire, where one sometimes needs a good deal of music to fill up the space before the service. It certainly makes waiting for brides or late-running relatives less of an endurance test. The four movements of this piece could be used as an extended service prelude, or broken up so that your congregation can enjoy it over a whole service. For the latter, I would suggest the following scheme for a Eucharistic service: the first and second movements for the prelude, the third for during communion, and the final movement as a sprightly postlude.

No comments:

Post a Comment